Ninth-grader Andrew Taate felt like he was in a deep hole, one he dug himself from his San Francisco bedroom as he procrastinated for months on school assignments, his motivation absent.

A straight-A student in middle school, Andrew started ninth grade in August at home, his classmates’ tiny faces in square boxes on his computer screen.

“It took a really big mental toll,” the 15-year-old Thurgood Marshall High School student said. He started missing assignments and failing classes, the growing backlog overwhelming him. “I felt a lot of guilt from it.”

He lost hope that he could academically recover.

In the wake of stay-at-home orders that pitched California students into academic and social isolation a year ago, countless students have endured similar mental health struggles. Families have watched as their previously motivated and chatty children became despondent, angry, listless, afraid — and, in some cases, suicidal.

The impact for many Bay Area families has been devastating, even life-altering.

The California Parent and Youth Helpline: 877-427-2736

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 800-273-8255

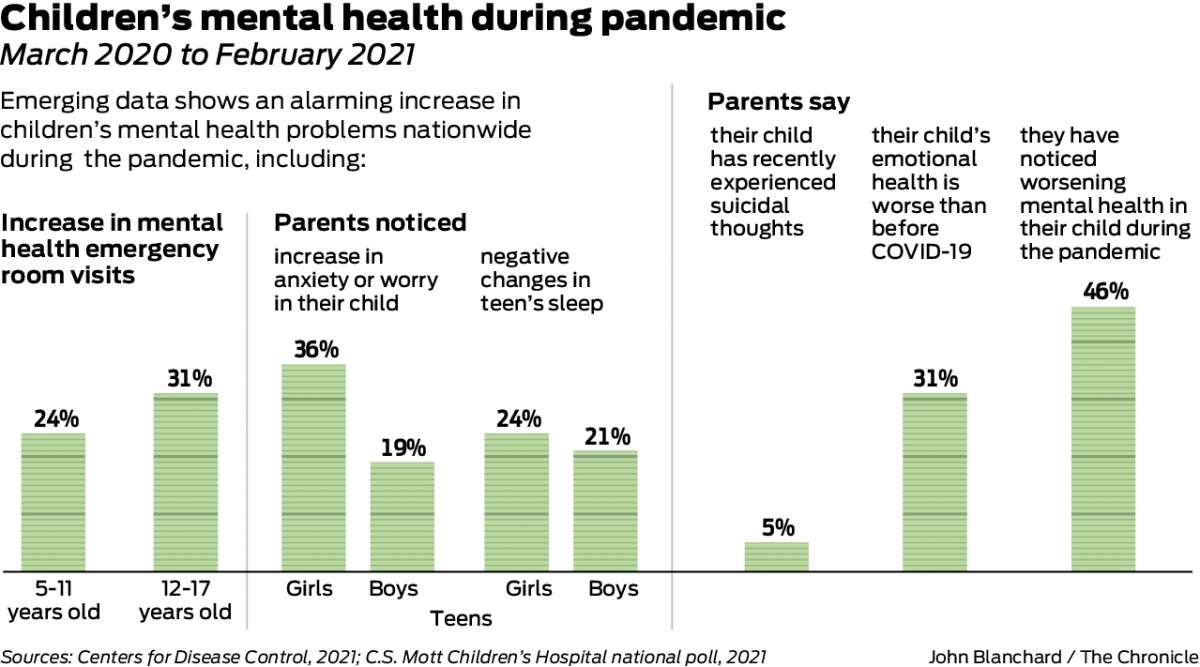

Emerging research shows a mental health crisis is unfolding among children, filling hospital emergency rooms and child psychiatric facilities while leaving overwhelmed pediatric therapists and counselors unable to take new clients.

For communities of color and families already struggling with poverty, their trauma is compounded, public health experts say, and they’re less likely to be able to access mental health resources.

The increase of children in crisis is striking. Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland saw 651 children seeking emergency mental health services from May to December last year, up from 368 during the same period in 2019, a 77% increase. And on average, more than seven children were hospitalized at any given time for eating disorders in 2020, more than double the number a year earlier.

Because of spiking demand, the capacity to treat these children is limited, with long waiting lists for licensed therapists and full psychiatric hospital beds.

Bay Area “child psychiatry beds are full and children are waiting days in the emergency room to be admitted to residential facilities,” a group of Berkeley health officials and medical experts wrote to the school district, urging schools to reopen. “And to put it candidly, those that come to our offices and our emergency rooms may be the lucky ones that are reaching out for help.”

As many classrooms start to reopen in the coming weeks, it’s unclear whether schools and the health care system will be ready to address the long-term mental health impact — in addition to the academic loss — for millions of children.

It will be up to school boards to determine whether to allocate resources to that, with billions of dollars in state and federal pandemic aid available to help districts address the academic and mental health needs of students.

For many young people, the past year has included “lifelong scarring experiences,” said Dr. Jeanne Noble, UCSF director of COVID-19 response.

“Every place you look — the signs of social phobia and isolation, all the way up to suicide attempts — screams crisis,” Noble said. “What is happening to the brain development of all these teenagers shut in their dark bedrooms on Zoom all the time? Even if they’re not suicidal, they are not going to come out unscathed.”

Nearly half of parents said they saw a “new or worsening mental health condition for their teen” since the start of the pandemic, according to a national survey in January by C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital at the University of Michigan.

Approximately a quarter of children ages 14 to 17 reported experiencing moderate to severe depressive symptoms in the fall, up from 13% in 2018, according to research by Common Sense Media.

San Francisco veteran teacher Lindsay Cutler has had a front-row seat to the devastating impact of the pandemic at Thurgood Marshall, where 60% of students are English learners and well over half are from low-income families.

Because of job losses at home, some attend classes from a homeless shelter. Others have taken up smoking marijuana because they can’t play basketball or other sports, Cutler said. Some have fallen completely off the radar.

“They all say the same thing, that school is their refuge from their home life and that’s gone,” she said.

Cutler said she has seen students with no history of mental health problems suffer so dramatically in the past year that they were hospitalized because they were deemed a danger to themselves or others.

Three weeks ago, Andrew Taate started climbing out of his academic hole, attending an informal gathering of teachers and students in the Thurgood Marshall courtyard every Wednesday.

Being at the school with teachers and other students lifted his spirits and motivation for the first time in months, he said on a recent morning as he sat at a table in the courtyard. He worked on missed assignments and set his sights on earning B’s, if not A’s.

For the first time in months, he has hope, he said.

Yet, few Bay Area high schools have such an option, and most Bay Area districts — including San Francisco — will not reopen middle and high schools to all students this spring.

Cutler, who is eager to return to in-person learning, worries the fall return will be too late for too many.

“I don’t know who is to blame,” she said. “It’s all infuriating.”

What the pandemic will mean for the mental health of young people over the long term remains to be seen. Research has repeatedly shown that social isolation can alter the brain and have an impact on cognitive function.

Dr. Emily Baldwin, a Berkeley psychiatrist, recounted the toll isolation is having on patients, including teens who can’t get out of bed, have developed eating disorders or have cut themselves. Some have attempted suicide.

For communities of color and families already struggling with poverty or other issues, the pandemic and social isolation have been even more traumatic, said Archana Basu, a clinical psychologist and epidemiology research scientist at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“Basically,” she said, “hard lives have become harder.”

In Oakland, district officials have begun reaching out to families to raise awareness about the impact of the pandemic on mental health.

“Our community has faced unbearable trauma as we lost loved ones, jobs, housing, and long-held routines and rituals that kept us safe and connected in our homes and communities,” Barb McClung, the district’s director of behavioral health, said in a letter to the community in late March. “There is much healing to do from the life-altering events we’ve experienced during this global health crisis.”

McClung reminded families that counselors, nurses and others are available to provide help and referrals for care.

Yet, meeting the mental health needs of children will also require an expansion and restructuring of the system to include a range of services, including in-person, group and online sessions, Basu said.

“How do we meet this emerging mental health need?” she asked. “We need people who can be the voices of the children.”

At Thurgood Marshall, assistant principal Sarah Ballard-Hanson is working on that. School leaders are interviewing students, prioritizing African American and Pacific Islander teens, to understand what they will need.

The administrator always worries about her students, many of whom have complex needs, but distance learning has multiplied that.

“We definitely see that struggle,” she said. “Students who just aren’t themselves, who have kind of retreated, who are not as jokey as they used to be.”

Educators across the region hope a return to classrooms and the critical health services and other resources offered at school will make the biggest difference — with most students learning and laughing again.

For others, the recovery will probably be much longer.

In Berkeley, mom A. Behn started to worry when her high school senior son, a 6-foot-3 “smartypants” who loved to eat, stopped joining the family for breakfast and lunch. The teen’s report cards, filled with A’s and the occasional B before the pandemic, now included D’s and C’s, with a real threat of failing coursework.

The outgoing athlete with a love of math was sometimes “almost catatonic,” she said.

The 17-year-old is spending his last year of high school grappling with what his doctors have recently diagnosed as major depressive disorder with anxious distress. He is on antidepressants and seeing a psychologist once a week.

Behn believes that more than a year of distance learning will have long-term repercussions on her son. While he recently got accepted into the Rochester Institute of Technology, he now must inform the university that he will not complete Berkeley High’s academically elite International Baccalaureate program.

The teen declined to speak in depth about the past year, but shared what he misses most about school.

“I mean, I miss seeing my friends,” he said. “I miss the solidarity that comes with everybody having hard assignments to do ... the structures of support that come with being a senior.”

His mom blames the reticence of the school district to reopen, despite gaining authorization from county and state health officials to do so months ago.

“I kind of want to sue the school district for pain and suffering,” she said. “I feel like this is another pandemic that we’ve brought upon ourselves in some way.”

Jill Tucker is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: jtucker@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @jilltucker