After a terrifying month that saw Covid-19 overwhelm the country’s run down health system, doctors and nurses on the pandemic frontlines say they were pushed into physical and mental exhaustion as they fought to keep their patients alive.

Mousimi Das had to treat her own mother in her Kolkata hospital as countless patients including a colleague’s father died around her, working 48 hours in one stretch without a break. She has one message for the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“We are exhausted, frustrated, and depressed,” Das said over phone, her voice breaking with fatigue. “Please see us. Please hear us. If you don’t listen to doctors, nurses and staff working on the ground, you will never be able to improve the health infrastructure.”

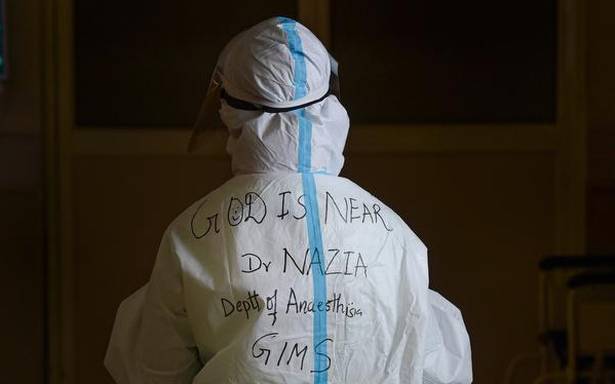

Das is not alone. Bloomberg spoke to a dozen doctors who described a nightmare scenario: continued high-risk exposure to the virus, a never-ending flow of patients and deaths and long hours in sweat-drenched PPE kits that made even washroom breaks difficult. It’s leading to burnout, anxiety and insomnia among a large number of India’s 1.3 million doctors and complicates the fight to contain the world’s worst coronavirus outbreak.

More than 1,200 doctors have lost their lives so far in a country that’s reported nearly 27 million Covid-19 cases, according to a toll maintained by the Indian Medical Association.

Chronic underfunding

Even before the pandemic hit India, its health sector was ranked 110 out of 141 countries, behind Bangladesh, Indonesia and Chile, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report 2019 found. The South Asian nation’s rural towns and villages, home to nearly 70% of India’s 1.4 billion population, have only a skeletal health infrastructure.

The number of doctors for every 10,000 people in India has fallen to around nine in 2019 from 12 in 1991, according to data on World Health Organization’s website, while the country’s health expenditure was just 3.54% of GDP, lower than countries including Iraq, Afghanistan, Egypt, China and Kenya.

India must now strengthen its health system by investing in hard infrastructure and human resources and making its data transparent, said Yamini Aiyar, the President of the New Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research.

“We are fighting the pandemic on the back of an extremely creaky and broken system,” Aiyar said, noting State and federal governments had missed the opportunity to improve health care and governance during the lull between the pandemic’s first and second wave. “That is one of the crucial reasons why health workers are under deep strain.”

Exhausted, Depressed

For doctors like Anita Gadgil, the head of surgery at a hospital in Mumbai, it is the sheer volume of death that is hard to bear. “Personal losses combined with the uncertain and distant seeming end of this pandemic is leading to helplessness and frustration among the doctors,” she said. “We are just living day-to-day and duty-by-duty.”

There is little support for those suffering burnout. Several doctors Bloomberg spoke to said they and their colleagues had increasingly turned to smoking and alcohol to numb their minds after long work shifts.

Bureaucratic red tape only adds to their difficulties.

Nurses in New Delhi went on strike in December to force the government-run All India Institute of Medical Sciences to pay three months worth of salaries they were owed. The industrial action only ended after a high court intervention forced the federal government to guarantee their wages would be paid.

In India’s most populous state of Uttar Pradesh, 16 doctors resigned en-masse last month from their roles in government health facilities after they were blamed by officials for the worsening virus situation, while resident doctors at four government hospitals in Mumbai threatened a hunger strike because they hadn’t received a mandated increase in their Covid duty payment. That increase has since been cleared.

Citing surveys and expenditure trackers maintained by the Centre for Policy Research, Aiyar said “poor quality public finance management” meant it was common practice for salaries to be bundled into six-month payouts rather than regular monthly wages, adding to an already stressful sitution.

Better salaries

A good health care plan, better salaries, decent quarantine facilities and safety equipment are essential to ensure medical staff are properly cared for, said Monali Mohan, a doctor who has worked with international non-government organizations on improving State-run health facilities.

“Delayed salaries or lack of monetary incentivization makes you think authorities don’t even think about the work they are doing,” Mohan said.

There are also safety concerns, with angry relatives often taking their frustration and grief out on health workers. Deaths due to shortages of medicines, oxygen, and hospital beds have made the situation worse.

In the last year, Das has faced death threats, rape threats, and has even had shoes thrown at her and her colleagues in the hospital. Talking of better insurance plans is far-fetched at this point, she said. “A little respect and staying safe would be enough.”