The latest one is the claim that we cannot raise the minimum wage during the COVID-19 recession. Raising the minimum wage during a recession, they say, will stall our recovery.

This might sound plausible for a second—or until one remembers that the minimum wage was created during the Great Depression by the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA). After a slow recovery from the Great Depression, the economy went into reverse in 1937 and the beginning of 1938.

The reason is clear.

In 1936, President Franklin Roosevelt started to listen to orthodox economists worried about the budget deficit. Taxes were raised, government spending was cut and the U.S. government had a balanced budget in 1937. The Federal Reserve raised interest rats as well, hurting the economy.

But the economy suffered. Unemployment, which was still high at 13.3 percent in May 1937, had jumped to 19% by June 1938. Manufacturing output fell by 37 percent from the 1937 peak.

In response, Roosevelt encouraged Congress to enact new spending programs and renewed his fight for the FLSA, which Congress passed an

Just like today, business people complained. Roosevelt responded the way we should respond today (with numbers adjusted for inflation): “Do not let any calamity-howling executive with an income of $1,000 a day, … tell you … that a wage of $11 a week is going to have a disastrous effect on all American industry.”

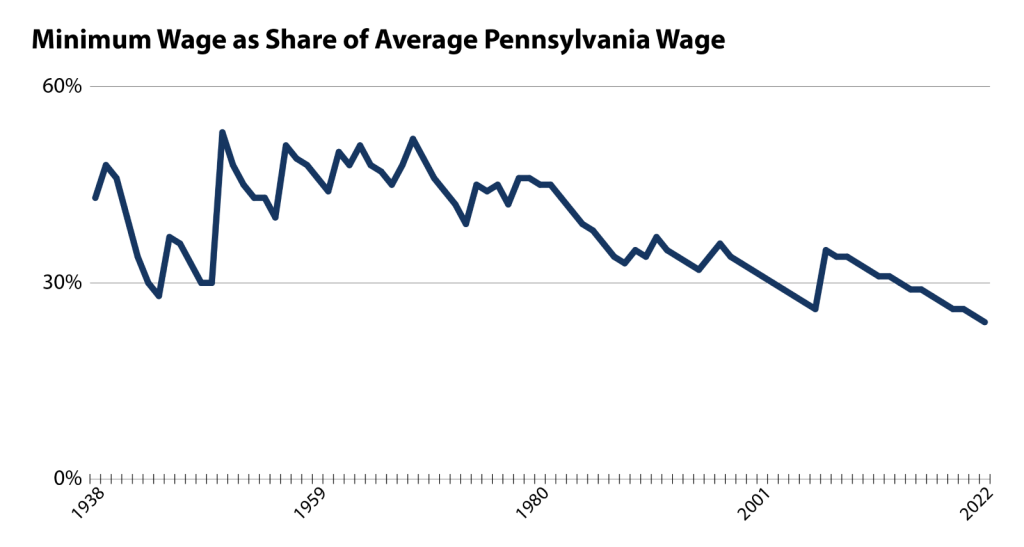

While the minimum wage did not apply to all workers, 25 cents an hour was a significant wage in 1938. Indeed, it was 42 percent of the average wage of Pennsylvania workers that year.

And increases in the minimum wage in subsequent years drove it up to 46 percent of the average Pennsylvania wage in 1940 and 52% in 1950. After dropping again, the minimum wage again rose to 52 percent of the average wage in 1968.

However, in the years since 1968 the minimum wage was not raised in step with inflation and is now at an all-time low of 25.1 percent of the average Pennsylvania wage.

A higher minimum wage, together with government deficit spendi

And the reason the minimum wage helped rather than hurt the economy in 1938 is the same reason it will help today: When wages go up, workers have the means to spend more in the local economy. It is consumer spending that drives our economy forward—and it is also what gives businesses a reason to invest more in productive capacity.

Far from hurting the economy, a $12 minimum wage on July 1, 2021, would add $4 billion to consumer spending in our state and a $15 minimum wage in 2027 would add $6 billion.

A $15 minimum wage is not out of line with past practice. A $15 minimum wage today would only be about 50% of the average wage in Pennsylvania and would be a bit lower by the time it is reached in 2027. That is below what the minimum wage / average wage ratio was at its height in 1950 and 1968. And 1968 was a year with historically low unemployment.

A wage at that level would do what the minimum wage was meant to do when the FLSA was enacted—quicken the pace of economic recovery and ensure that all working people—including the many adult, full-time workers with children who work for the current minimum wage —have a decent standard of living. Pennsylvanians deserve that in 2021, just as they did in 1938.

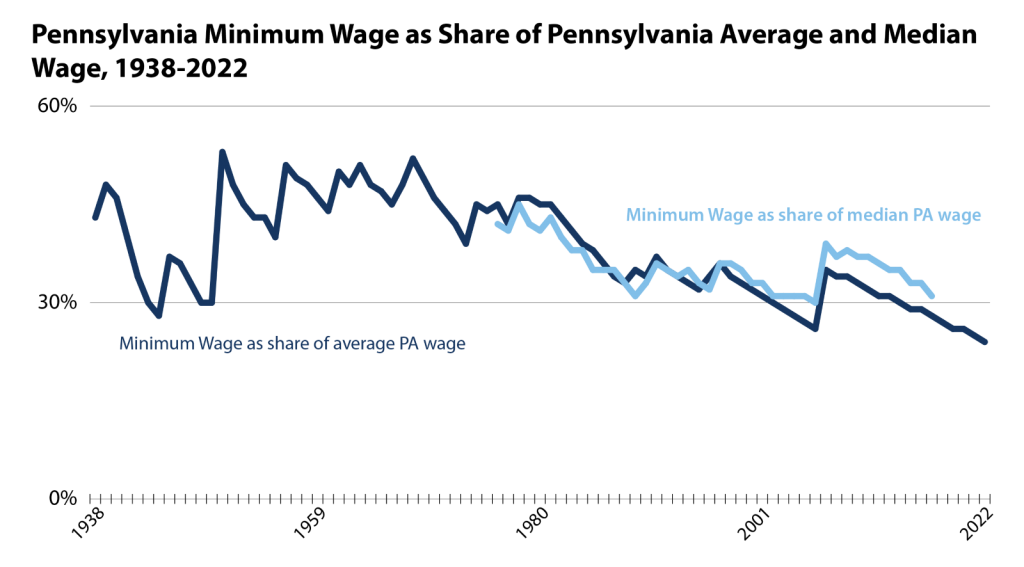

A note on the data: It is generally preferable to compare the minimum wage rate to the median wage, not the average wage an increase in inequality could, by itself, lead to an increase in the the average wage.

Averag

But we do not have historical data for median wages in Pennsylvania prior to 1968, thus the table above presents the ratio of the minimum wage to the average wage.

The following table, however, adds a second line with the ratio of minimum wage to the median wage in Pennsylvania. The two data series track closely, giving us more confidence in the minimum to average wage data.

Marc Stier is the director of the Pennsylvania Budget & Policy Center, a progressive think-tank in Harrisburg. His work appears frequently on the Capital-Star’s Commentary Page.

Marc Stier is the director of the Pennsylvania Budget & Policy Center, a progressive think-tank in Harrisburg. His work appears frequently on the Capital-Star’s Commentary Page.