Summary

Background

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in people with pre-existing mental health disorders is unclear. In three psychiatry case-control cohorts, we compared the perceived mental health impact and coping and changes in depressive symptoms, anxiety, worry, and loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic between people with and without lifetime depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders.

Methods

Between April 1 and May 13, 2020, online questionnaires were distributed among the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety, Netherlands Study of Depression in Older Persons, and Netherlands Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Association cohorts, including people with (n=1181) and without (n=336) depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders. The questionnaire contained questions on perceived mental health impact, fear of COVID-19, coping, and four validated scales assessing depressive symptoms, anxiety, worry, and loneliness used in previous waves during 2006–16. Number and chronicity of disorders were based on diagnoses in previous waves. Linear regression and mixed models were done.

Findings

The number and chronicity of disorders showed a positive graded dose–response relation, with greater perceived impact on mental health, fear, and poorer coping. Although people with depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders scored higher on all four symptom scales than did individuals without these mental health disorders, both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, they did not report a greater increase in symptoms during the pandemic. In fact, people without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders showed a greater increase in symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas individuals with the greatest burden on their mental health tended to show a slight symptom decrease.

Interpretation

People with depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders are experiencing a detrimental impact on their mental health from the COVID-19 pandemic, which requires close monitoring in clinical practice. Yet, the COVID-19 pandemic does not seem to have further increased symptom severity compared with their prepandemic levels.

Funding

Dutch Research Council.

Introduction

,

With worries about future uncertainty, concern has been growing about the mental health sequelae of the COVID-19 crisis.

Most evidence on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health is based on convenience samples, without comparable prepandemic information, thus compromising the validity of this evidence.

So far, based on probability samples, a rise in psychological distress in April, 2020, compared with in 2018–19, has been reported among adults in the USA

and the UK.

,

Financial instability and small social networks are common among people with mental illness; as a result of economic recession and restricted social connectivity, the COVID-19 pandemic could present an unprecedented stressor to these individuals.

Measures such as nationwide travel restrictions and quarantine, and changes in the way health-care services are provided, could interrupt access to and provision of psychiatric care.

,

As a result, the risk of relapses or worsening of existing mental health conditions could rise during the COVID-19 pandemic. There is an urgent need to empirically understand to what extent the COVID-19 pandemic and related societal changes have so far affected the mental health of people with pre-existing mental health disorders.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed and Google Scholar with the terms (“mental*” OR “psychiatr*”) AND (“COVID*” OR “coronavirus”) for articles published in English between Jan 1 and Sept 30, 2020. All studies identified by our search and focusing on the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with mental health disorders either used a cross-sectional survey, relied on self-reported mental health, or had no prepandemic baseline data at the individual level.

Added value of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first dataset based on existing psychiatry case-control cohort studies with information on the mental health of the same individuals for more than 10 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The burden of depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders, in terms of both number and chronicity of disorders, had a graded dose–response relation with perceived mental health impact, fear of COVID-19, and poorer coping during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although our study did not show any signs of a further increase in symptom severity in people with depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic, the mental health of these individuals was and remained systematically worse than that of people without these disorders.

Implications of all the available evidence

This finding emphasises the importance of providers maintaining access to mental health-care services for people with pre-existing disorders. Since development of the COVID-19 pandemic is constantly changing, it is necessary to continue monitoring its long-term effect on mental health in people both with and without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders, along with the effect of strategies that aim to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

more symptoms of depression and anxiety, stress, and insomnia were reported among people with psychiatric disorders than among individuals without a mental health disorder. In an Australian non-probability sample,

psychological distress was higher among people with self-reported mood disorders than among those without. However, symptoms before the COVID-19 pandemic were not measured in these studies, leaving it unclear whether the pandemic truly led to changes in symptom levels within populations with psychiatric disorders.

We did a study using longitudinal data from three existing Dutch psychiatry case-control cohorts, including people with and without mental health disorders (depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders). Data collection for the three cohorts started in the early 2000s, and the most recent information from the same individuals was collected 2–8 weeks after the national lockdown in the Netherlands. We aimed to compare between people with a different number and chronicity of mental health disorders the perceived impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and the extent to which individuals were able to positively cope with the situation, and changes in symptoms of depression, anxiety, worry, and loneliness from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Participants

Netherlands Study of Depression in Older Persons (NESDO),

and Netherlands Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Association Study (NOCDA).

The largely similar procedures for data collection in these cohort studies allowed pooling of data for our study.

Between 2004 and 2007, participants were recruited from the community, primary care, and specialised mental health care in the Netherlands, and they were followed up after 2, 4, 6, and 9 years.

From 2007 until 2010, 378 individuals with a depressive disorder were recruited through specialised mental health-care services. People without lifetime diagnoses of depression, anxiety, dementia, or another clinically overt psychiatric disorder such as psychosis, severe addiction, or bipolar disorder (n=132) were recruited from primary care. Face-to-face assessments were done after 2 and 6 years.

Baseline assessments were done between 2004 and 2009, and follow-up examinations took place after 2, 4, and 6 years.

Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Vrije Universiteit Medical Center, Amsterdam, and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent online.

Procedures

Table 1Data availability in previous regular waves by cohort

NESDA=Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety. NESDO=Netherlands Study of Depression in Older Persons. NOCDA=Netherlands Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Association Study. QIDS=16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms. BAI=21-item Beck Anxiety Inventory. PSWQ=11-item Penn State Worry Questionnaire. DJGLS=six-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale. CIDI=Composite Interview Diagnostic Instrument. SCID=Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders.

in NOCDA, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders was used for diagnosis.

Lifetime and current (within the past 6 months) presence of six disorders was assessed at all previous waves in all three cohorts: major depressive disorder, dysthymia, general anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and agoraphobia. The diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder was added in NOCDA only. We used longitudinal data to classify the overall burden of mental health disorders in two indicators: severity and chronicity. For severity across disorders, we calculated the total number of different lifetime mental health disorders an individual has been diagnosed with, because this number provides an integrative measure, and it has been consistently shown that comorbidity of mental health disorders (ie, having more disorders) is related to higher specific symptom severity and overall disability.

,

For chronicity, we divided the number of waves with a current diagnosis (regardless of type of disorder) by the number of waves an individual participated in and categorised into zero, less than or equal to half, and more than half of all waves with a current disorder.

for anxiety symptoms the 21-item Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI);

for worry the 11-item Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ);

and for loneliness the six-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (DJGLS).

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the study population were compared between people with and without lifetime mental health disorders using either the χ2 test or the t test. We deemed a p value less than 0·05 statistically significant.

When there was only one measurement available in the previous waves, that value was used. We used mixed models with random intercept to compare changes in QIDS, BAI, PSWQ, and the DJGLS from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic across groups. Interaction terms of time and group indicated whether changes in symptoms differed across groups. We obtained estimated marginal means to quantify changes in symptoms by the number and chronicity of mental health disorders.

In addition to reporting results using original scores of the dimension scales and symptom severity scales, we also presented results using forest plots, in which standardised scores were used that enabled easier comparison of trends among different outcomes. All models were adjusted for age, gender, education, living situation, and the date of the response.

Several separate supplementary analyses were done. To limit the potential effect of differences in assessment timeframe after the COVID-19 outbreak, we focused on information obtained within April, 2020 (n=1427). To eliminate the potential effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection on mental health, we repeated analyses in people not diagnosed with COVID-19 (n=1500). Analyses were rerun after not considering a diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder in mental health disorder status because it was selectively available. We also did stratified analyses by age 50 years, gender, and source study.

The descriptive analysis and EFA were done in SPSS version 22. The ICC function from the DescTools R package (version 0.99.28) was used to obtain ICCs. We used packages in R (version 3.6.0) for linear regression and mixed models (lme4, version 1.1–21; emmeans, version 1.4.3.01) and for figures (forestplot, version 1.9).

Role of the funding source

The funder of this study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. All authors had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Between April 1 and May 13, 2020, online questionnaires were sent out every 2 weeks to 2748 living participants in the three studies who gave permission to be contacted for further research activities. After excluding 110 individuals who could not be contacted, most (85%) participants were from NESDA (n=2245), with 4% from NESDO (n=108), and 11% from NOCDA (n=285). 1517 (58%) participants filled in the online questionnaire at least once. We used the first response per respondent. Compared with respondents, non-respondents were younger (p<0·0001) with a lower education level (p=0·0017), and they were more likely to have a pre-existing mental health disorder (p=0·029), but they did not differ by gender (p=0·54).

Table 2Characteristics of study population by lifetime mental health disorder

Data are mean (SD) or n (%). Lifetime mental health disorders included depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders. NESDA=Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety. NESDO=Netherlands Study of Depression in Older Persons. NOCDA=Netherlands Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Association Study.

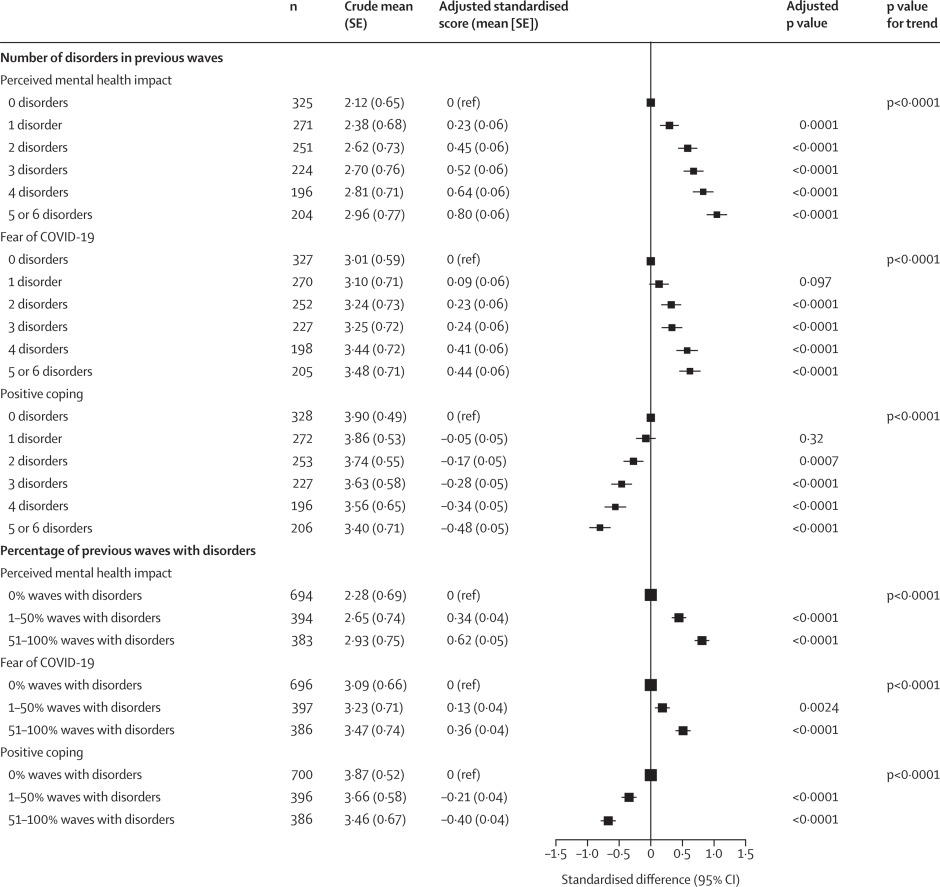

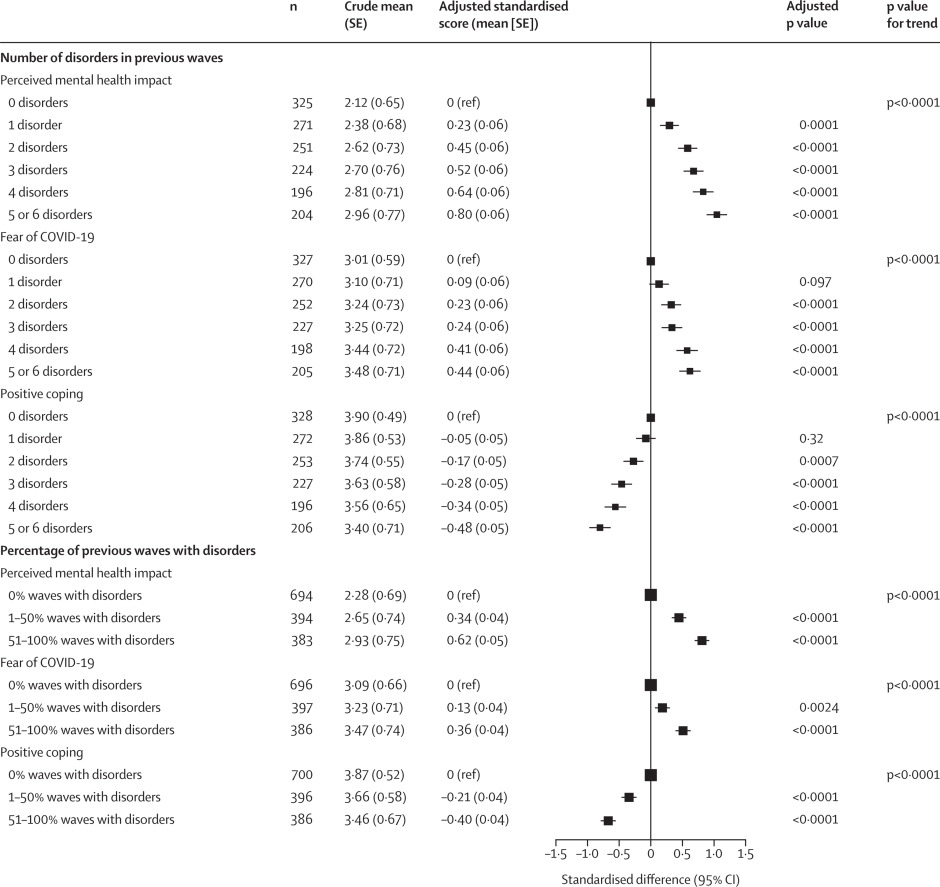

Figure 1COVID-19-specific dimensions in relation to severity and chronicity of depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders

Severity is the number of lifetime disorders. Chronicity is the percentage of previous waves with current disorders. The crude mean refers to the mean score in each dimension by mental health disorder status. To create the forest plot, each COVID-19-specific dimension score was standardised. The adjusted standardised score was derived from linear regression, adjusted for age, gender, education, living situation, and date of response.

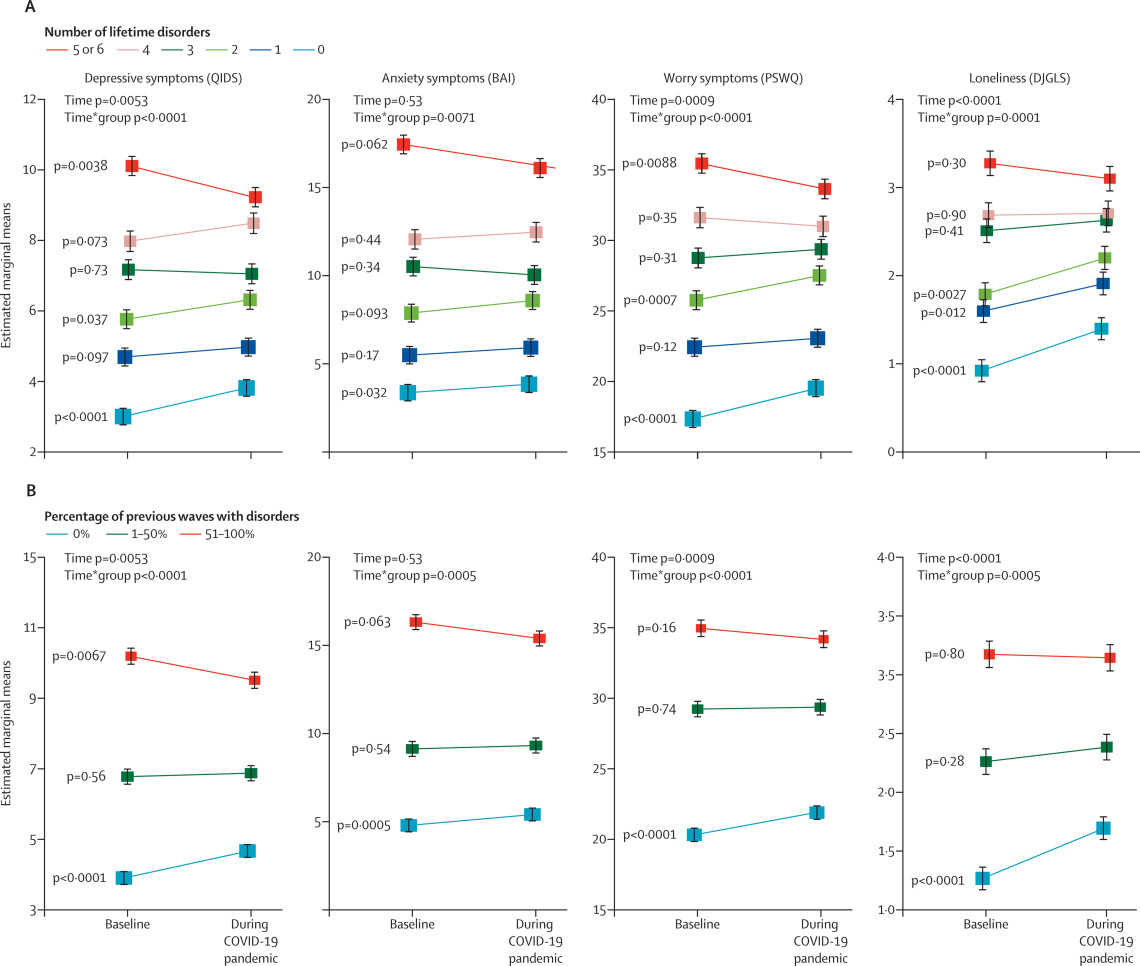

Figure 2Trajectories of symptom severity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to severity and chronicity of depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders

Severity is the number of lifetime disorders (A). Chronicity is the percentage of previous waves with current disorders (B). Baseline levels refer to average scores of QIDS, BAI, PSWQ, and DeJong Q in the preceding waves before the COVID-19 pandemic. Mixed models were adjusted for age, gender, education, living situation, and date of response. Data are mean; error bars show the SE. QIDS=16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms. BAI=21-item Beck Anxiety Inventory. PSWQ=11-item Penn State Worry Questionnaire. DJGLS=6-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale.

Our findings remained robust in all supplementary analyses. Stratified analyses by age 50 years, gender, and source study showed similar trends across strata.

Discussion

In our longitudinal study of three Dutch psychiatry case-control cohorts, we noted a graded dose–response relation between the number and chronicity of depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders and perceived mental health impact of COVID-19, fear of the virus, and poorer ability to cope, during the first few weeks after the national lockdown in the Netherlands. Both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, levels of symptoms of depression, anxiety, worry, and loneliness were systematically higher in people with multiple and chronic mental health disorders. However, we did not find evidence that there was a strong increase in symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in those with a higher burden of disorders. In fact, changes in scores from before to during the pandemic indicated increasing symptom levels in people without mental health disorders, whereas changes of symptom levels were minimal or even negative in individuals with the most severe and chronic mental health disorders.

,

The current study is among the first to assess symptoms in the same individuals both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. For people with severe or chronic mental health disorders, the COVID-19 pandemic did not seem to exacerbate their pre-existing high levels of symptoms. However, the levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, worry, and loneliness increased more in people with no or less severe or chronic mental health disorders. Although this finding could suggest a potential increased need of mental health care among people without mental health disorders, the increase of symptoms seemed rather modest. As such, the elevated symptom levels among this population might partly represent a normal sadness and fear response to an unprecedented crisis.

Second, staying at home could help them build a structured and fixed daily routine, which has been expressed as a preferable setting to provide a feeling of safety.

Third, the decrease in depressive symptoms and worry might be attributable to regression to the mean and recovering due to the naturalistic course of mental health disorders.

However, prepandemic symptom severity levels were based on average scores across the preceding waves covering many years.

Data collection is currently ongoing and will enable us to track longitudinal changes in the four symptom dimensions and the perceived mental health impact and coping during the longer pandemic trajectory and beyond the national lockdown.

Some study limitations need to be acknowledged. First, different modes of data collection were applied during the previous waves in 2006–16 (face-to-face interviews) and for the COVID-19 questionnaire (completed online). However, this difference applied to all respondents, thereby it probably does not cause differential associations by psychiatric status. Second, the response rate (58%) of the online questionnaire was rather low. Non-respondents were more likely to have a pre-existing mental health disorder, which could affect our findings by underestimating the mental health impact on individuals with mental health disorders. Third, no standardised assessment tool was applied to ascertain mental health disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, we evaluated the severity and chronicity of mental health disorders based on previous waves of the three cohort studies. Assessment timeframes of the four symptom severity scales differed between NESDA, NESDO, and NOCDA; thus, caution is warranted when comparing trajectories of these scores. Finally, our approach of measuring severity across disorders by counting the number of disorders might not be optimal. However, we found that the association between each type of disorder and mental health outcomes was similar and that there was a graded dose–response relation between the number of disorders and symptom severity, suggesting that counting the number of disorders was a good way to distinguish meaningful psychiatric subgroups.

The strengths of our study include well characterised psychiatric status (based on several diagnostic interviews) and use of COVID-19-specific items and four validated symptom scales to assess multiple dimensions of emotional response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study is among the first to relate longitudinal mental health data from more than 10 years before the COVID-19 pandemic within the same individuals to symptom levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. These long-term data allowed for a valid check on the true changes in mental health symptoms due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In summary, although the symptom severity of people with depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders was systematically higher compared with individuals without mental health disorders, pre-existing illness seemed to not necessarily predispose to a greater level of emotional reactivity to the COVID-19 pandemic during the first few weeks of national lockdown in the Netherlands. Future work is warranted to track the long-term effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in people with and without mental health disorders as the pandemic developed and with implementation of transmission mitigation strategies.

All authors had the idea for the study. K-YP and AALK wrote the initial analysis plan, with input from all other authors. K-YP, AALK, and EJG did the data analysis. AALK and EJG produced the figures. K-YP wrote the first draft of the report, and all other authors contributed to editing and commenting on the final version. BWJHP obtained research funding.

BWJHP reports grants from Janssen Research and Boehringer Ingelheim, outside of the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments