Adolescents have experienced a pronounced increase in symptoms of depression during a year of isolation and school closures, according to survey evidence released today. The research indicates that many have turned to digital health resources, as well as social media, to cope with the negative emotions stoked by COVID.

The survey — administered between last September and November through a partnership between nonprofit organizations Common Sense Media, Hopelab, and the California Health Care Foundation — contacted a representative sample of roughly 1,500 Americans between the ages of 14 and 22 both online and over the phone. To solicit detailed answers, researchers asked open-ended questions about respondents’ personal experiences with mental health and internet use during the pandemic.

The results, particularly those related to student wellbeing, are largely in keeping with other research that has emerged over the last year. A report conducted last summer by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that younger adults reported “disproportionately worse mental health outcomes, increased substance abuse, and suicidal ideation.” Doctors have also expressed concern that a shocking spate of suicides may be related to the disconnection felt by teens as they navigate months apart from their teachers and classmates.

In the survey released today, 38 percent of teenagers and young adults reported experiencing symptoms of moderate-to-severe depression, a disturbing increase from 25 percent who said the same in a similar poll administered by Hopelab in 2018. That climb was especially evident in the sample’s older students (aged 18-22), 48 percent of whom reported moderate-to-severe symptoms in 2020. While starting from a lower level in 2018, the proportion of younger children (aged 14-17) reporting such symptoms almost doubled, from 13 percent to 25 percent, over the same period. Overall, the proportion of participants reporting no or very few depressive symptoms fell from 52 percent in 2018 to 37 percent last year.

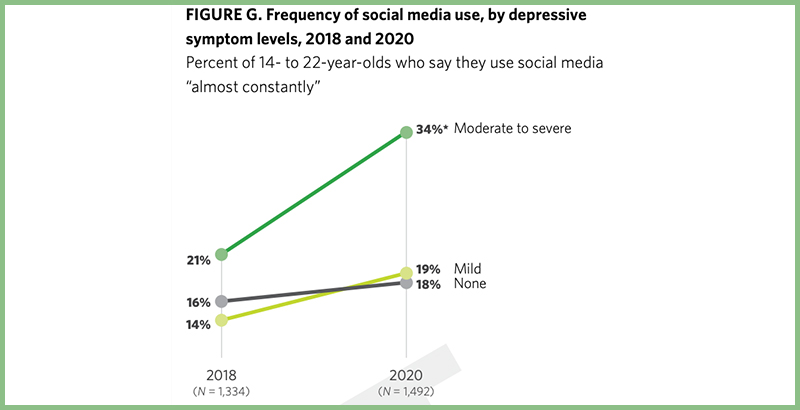

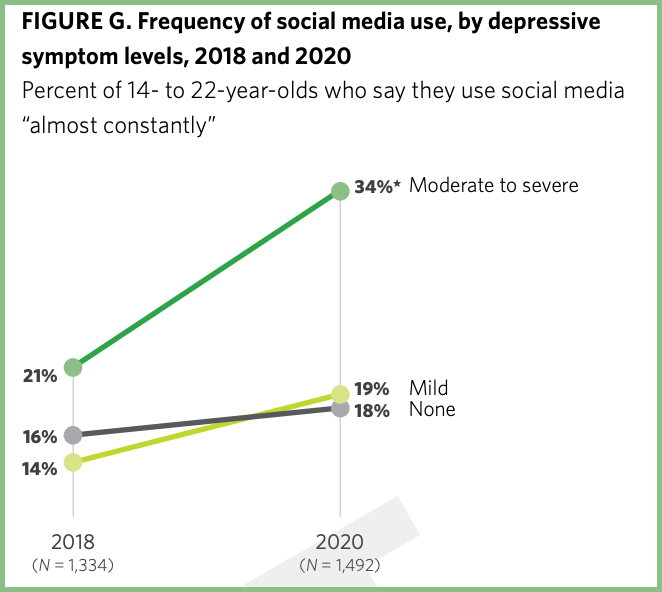

As in the 2018 survey, much of the analysis looks at patterns in internet use among adolescents reporting a variety of mental states. In both studies, participants reporting higher levels of depressive symptoms were more likely to say they used social media “almost constantly” than those with mild or no symptoms; but the gap between those classifications grew significantly in 2020, accounting for more than a third of respondents experiencing mild-to-severe symptoms of depression.

Study co-authors Victoria Rideout and Susannah Fox make no causal claims about the connection between social media use and mental health problems, though several theories circulated even before the pandemic began. One, advocated by psychologist Jean Twenge and others, postulates that too-frequent use of platforms like Snapchat and Instagram leads teenagers to “compare and despair,” triggering depression and anxiety. Another essentially makes the inverse argument, that the most afflicted people are driven by boredom and inactivity to spend hours scrolling through social media.

After looking over hundreds of survey responses from students in high school and college, Rideout offered a third possibility: that young people are connecting with peers and health professionals online to “proactively protect their wellbeing.”

“They are using technology to find other young people who are going through the same kinds of situations and get support from them, get advice, get inspiration,” Rideout said in an interview. “Especially during COVID, I think social media and other digital tools can be a lifeline for young people who are struggling with mental health issues.”

Forty-three percent of respondents said that using social media when stressed, depressed, or anxious made them feel better, compared with just 17 percent who said it made them feel worse. That gap has grown by 14 points since 2018.

In addition, a large majority said that they consulted online resources for information on a range of health and wellness issues, with many also using mobile apps for the same purpose. Nearly 60 percent said they had researched COVID-19, while anxiety, stress, and depression were all among the most commonly researched topics. Among young people who were identified by a screening tool as being at risk of drug or alcohol abuse, 46 percent said they had looked up information about those problems online, while 60 percent said they had connected with health providers. Among participants with symptoms of moderate-to-severe depression, 58 percent said they’d connected with health providers online, and 51 percent said they’d searched online for people with health concerns similar to their own.

Over a year into the pandemic, millions of teenagers and young adults still lack reliable home access to the internet — a digital divide highlighted in survey responses from several participants, who said they had trouble connecting with therapists and counselors over the internet. Rideout said she was worried that a lack of digital equity could be as damaging to student mental health as it has been to educational outcomes.

“I think that technology has become a lifeline for education and a lifeline for health for young people. They’re both important and, obviously, deeply connected. When a quarter of the high school-aged students are suffering from moderate-to-severe depression, their learning is probably not going to be optimal.”