Image credit: Shutterstock

The last few years have seen a renewed interest in psychedelics in clinical research, especially for mental and psychological illnesses. Subsequently, investment in psychedelic research is beginning to boom.

Psychedelic drugs and substances have had an interesting and meandering journey to get to where they are today.

Humanity’s connection to psychedelics for recreational and medicinal use dates back thousands of years. Western medicine only twigged to their potential to enhance psychotherapy in the 1950s and 1960s, particularly LSD and psilocybin, the active ingredient found in magic mushrooms.

Unfortunately, the “swinging 60s” and the rise of hippy counterculture saw the substances seep onto the streets and became popular drugs for recreational use. This led to them becoming stigmatised, politicised and in the 1970s, illegalised being declared Schedule I drugs in the US — substances with high abuse potential and no accepted medical use. Consequently, any promising research into their clinical uses came to a grinding halt.

The FDA’s landmark approval of Johnson & Johnson’s ketamine-derived nasal spray, Spravato for depression in March 2019 may have helped open the floodgates for other controversial drugs commonly used recreationally but with significant therapeutic potential.

Now a spate of new clinical trials looking into various psychedelic compounds in conjunction with intensive psychotherapy are underway or have been completed highlighting promising preliminary results.

These trials are underscoring a therapeutic one-two that is garnering increasing recognition – administering a mind-altering drug in combination with care from a trained therapist.

Many of the researchers and scientists carrying out studies in psychedelics believe they have the potential to ‘reset the brain’ thus helping it to break long-entrenched cycles and thought patterns associated with severe depression and addiction.

Clinical Trials Arena takes a look at some of the groundbreaking clinical trials that are paving the way for this new approach to treating mental health disorders.

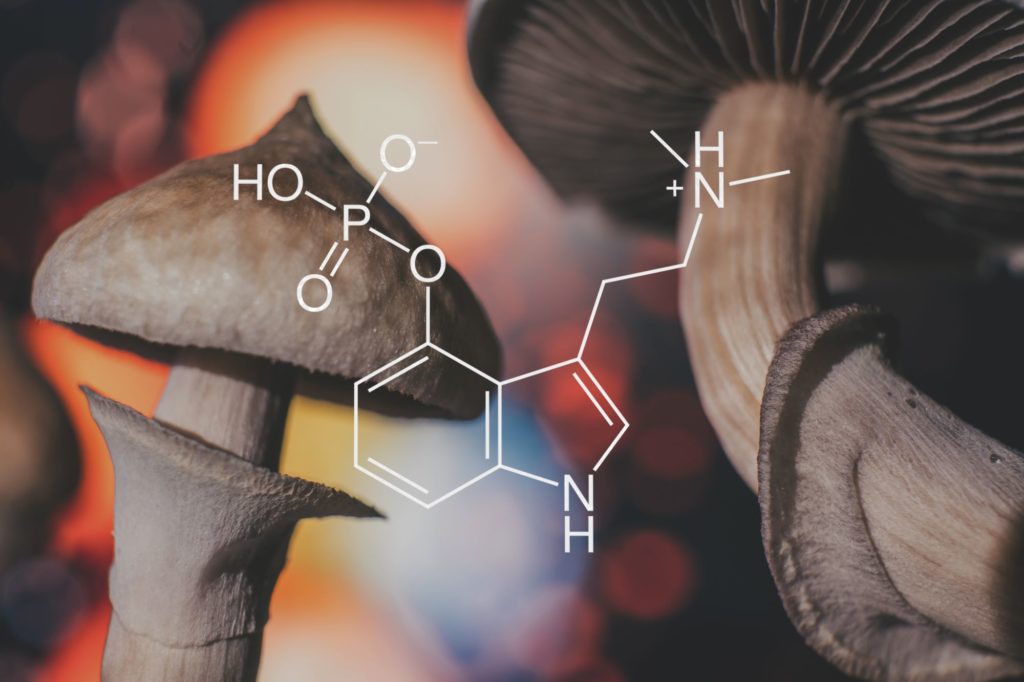

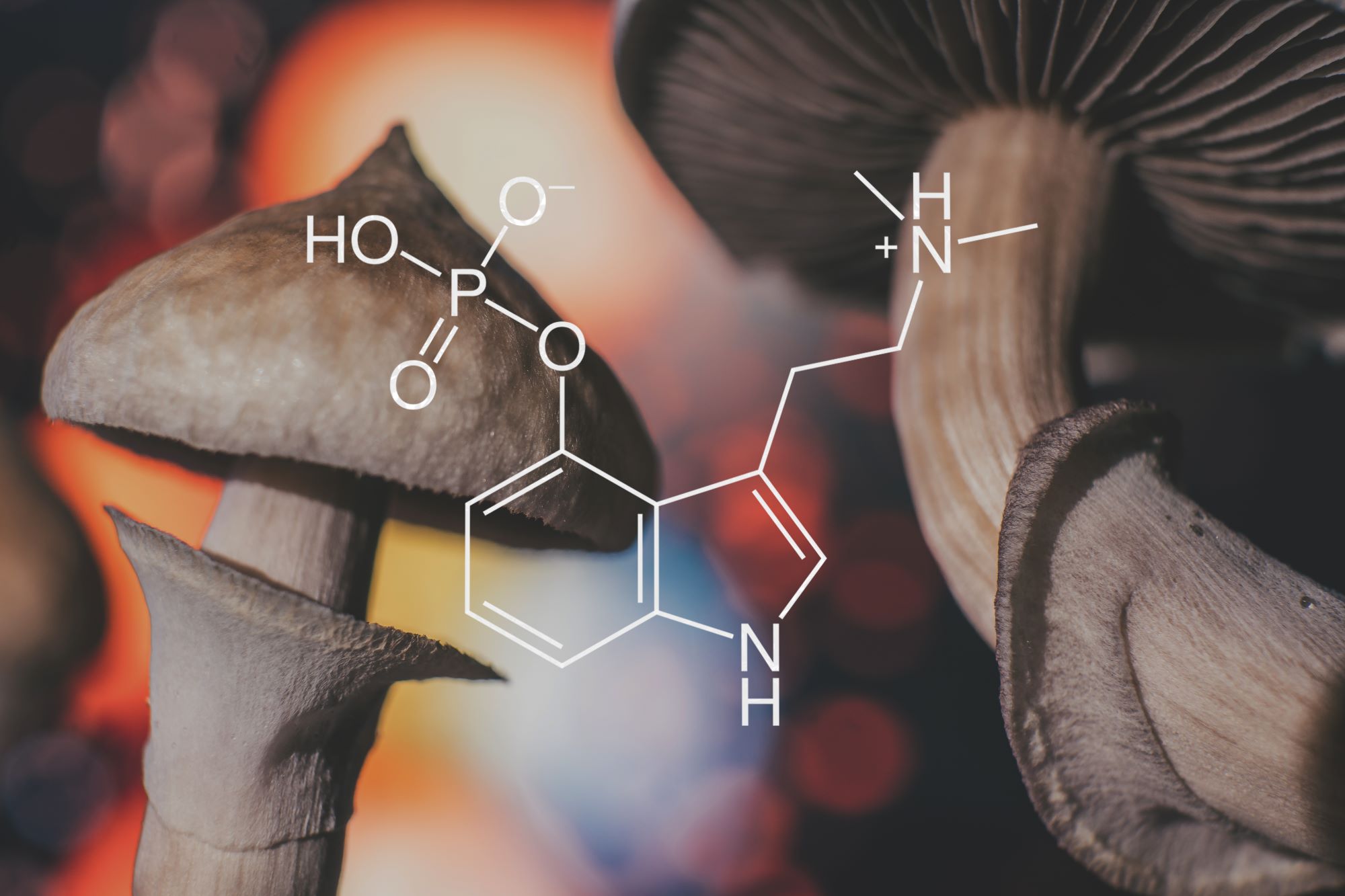

Psilocybin

Origin: Mushrooms found in Mexico

Indication: Major depressive disorder

Phase: Phase II

Sponsor: Imperial College London

In 2019 a modest group of researchers at Imperial College London established the Centre for Psychedelic Research, the world’s first dedicated centre for research into the mechanisms of action and clinical potential of psychedelic compounds.

The same year, a first-of-its-kind trial commenced out of the centre that saw a common antidepressant pitted against psilocybin to see if the substance could do a better job of battling depression.

The psilocybin formulation used in the trial was developed by UK company Compass Pathways, which received a breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA in 2018 for its earlier study of treatment-resistant depression.

The Phase II, double-blind, randomised, controlled Imperial trial involved 59 patients with long-standing, moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder (MDD). The study compared a psilocybin formulation against Lundbeck’s Lexapro (escitalopram), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, over six weeks. 30 were assigned to the psilocybin group and 29 to the escitalopram group.

Patients were assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive two separate doses of 25mg of psilocybin three weeks apart plus six weeks of daily placebo (psilocybin group) or two separate doses of 1mg of psilocybin three weeks apart plus six weeks of daily oral escitalopram (escitalopram group).

All of the patients in the study received intensive psychological support throughout.

The trial was run by Professor David Nutt, who was notoriously fired as the UK’s chief drugs advisor in 2009 after stating that alcohol and cigarettes were more dangerous than cannabis.

Nutt, who believes that psilocybin could revolutionise depression treatment by disrupting the areas of the brain that cause it, has said: “The criminalisation and banning of psychedelics is the worst censorship of research – not just medical research, but research – in the history of the world.”

The study found no statistically significant difference between the groups on depression scores using the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS-SR-16) scale, suggesting the two therapies worked as well as each other. However, the researchers also carried out other assessments of well-being, in which psilocybin appeared to come out on top.

This prompted critique from outside experts who claimed that the study design made it impossible to identify whether the psychedelic was actually more effective than escitalopram with regard to other measures of well-being.

“In hindsight I wish we’d made these other measures of well-being the primary outcome measure,” said Imperial Centre for Psychedelic Research head Dr Robin Carhart-Harris. “However the world — the Food and Drug Administration, the European Medicines Agency — doesn’t recognise those measures as valid.”

In a BBC documentary about the study participants, had positive things to say about their psilocybin experience, with one saying that the treatment meant she “felt like me again”.

3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)

Origin: Psychoactive drug derived from safrole oil

Indication: Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Phase: Phase III

Sponsor: MAPS

In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-site Phase III clinical trial to test the efficacy and safety of MDMA-assisted therapy for the treatment of patients with severe PTSD, researchers reported that two-thirds (67%) of treated participants no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis after 18 weeks and three sessions.

The trial, funded and run by the nonprofit Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), also found that 88% of people had a “meaningful reduction in symptoms”.

Talking therapy alone led to a significant improvement in 60%, and remission in 32% of people.

Patients in the study, the findings from which have been published in Nature Medicine, had been battling PTSD for an average of 14 years.

MDMA, popularly known as ecstasy, doesn’t induce the kind of vivid hallucinations associated with LSD or psilocybin, but rather boosts the brain’s levels of a number of neurotransmitters, including serotonin and dopamine, to create a sense of well-being and heightened empathy.

The trial’s researchers believe this might allow trauma survivors who face intrusive flashbacks to reflect on painful memories with less dread and self-judgement. “It gives you this fascinating ability toward self-compassion,” said the University of California, San Francisco neuroscientist and MAPS trial investigator Jennifer Mitchell.

MDMA was also found to be equally effective in participants with comorbidities that are often associated with treatment resistance.

MAPS hopes to confirm the results in an ongoing second Phase III trial and seek FDA approval for the therapy as early as 2023. The agency granted MDMA breakthrough designation in 2017, which comes with additional guidance during the trial process and an expedited review.

Ibogaine

Origin: Iboga shrub

Indication: Opioid addiction

Phase: Phase I/IIa

Sponsor: DemeRx and Atai Life Sciences

In March 2021, a joint venture between DemeRx and Atai Life Sciences was cleared by the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to start enrolment for a Phase I/IIa trial of ibogaine HCl (DMX-1002) in the treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD).

The opioid crisis is a critical unmet medical need, particularly in the US. In 2018 alone, 2.1 million Americans met the diagnostic criteria for OUD and 47,600 people died from opioid overdoses.

For those attempting to overcome opioid addiction, recovery is often thwarted by the current treatments available. Drugs like methadone or buprenorphine carry a high risk of abuse and come with side effects.

Ibogaine is a naturally occurring psychoactive compound isolated from a West African shrub called iboga, which has shown evidence of rapid and sustained efficacy in treating opioid use disorder (OUD).

The psychedelic has previously been marketed as a stimulant and antidepressant in France and studied elsewhere for addiction treatment including a large study led by DemeRx CEO Dr Deborah Mash in St. Kitts, West Indies.

“Not only were patients able to safely and successfully transition into sobriety, we found no evidence of additional abuse potential,” said Mash. “Given the limitation in currently available treatments, ibogaine represents an enormous leap forward for OUD sufferers.”

Phase I of the MHRA-approved trial is set to take place at the Manchester clinical unit of MAC Clinical Research (MAC), one of Europe’s largest independent clinical development organisations.

DMT

Origin: Plants including the South American plant chacruna

Indication: Major depressive disorder

Clinical trial: Phase I/IIa

Sponsor: Small Pharma

Earlier this month, Small Pharma, a UK-based neuropharmaceutical company focused on psychedelic-assisted therapies, announced the expansion of its Phase I/IIa clinical trial for its lead product, SPL026, a N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)-based treatment for MDD.

DMT is a powerful hallucinogenic found in numerous plants, including the South American shrub chacruna. When used recreationally or shamanistically it is brewed with the ayahuasca plant to make a tincture of the same name.

“Psychedelics have been shown to have therapeutic benefits in disorders such as depression, substance abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder,” said Small Pharma. “These so-called ‘internalizing disorders’ are characterized by debilitating flows of recurring negative thoughts.

“Clinical research suggests that DMT will break or disrupt the neuronal pathways that underlie these negative thought processes and by doing so, may facilitate the benefits of therapy given in combination with DMT. DMT-assisted therapy targets the root cause of depression and other ‘internalising’ conditions and has the potential to provide a treatment with rapid onset and a long duration of activity following treatment.”

The blinded, two-part Phase I/IIa clinical trial commenced in Q1 2021 and is being led by Hammersmith Medicines Research in London.

Phase I of the study aims to demonstrate the safety and tolerability of different dose levels of SPL026, a DMT fumarate, in ‘psychedelic-naïve subjects’ when compared to placebo. Phase IIa aims to affirm the patient proof-of-concept and will assess the efficacy, safety and tolerability of one versus two doses of SPL026, in combination with psychotherapy, in patients with MDD.

Efficacy will be evaluated using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale to measure the severity of depressive episodes.

Small Pharma has appointed MAC to expand the Phase IIa trial with an additional study site at Prescott, Liverpool, UK. This has helped bring the total number of participants in the trial to 42 and will mean that top-line results could be brought forward from the end of 2022 to the first half of 2022.

The firm’s CEO Peter Rands believes DMT will have an advantage over other psychedelic therapies as it can provide a short, powerful psychoactive experience lasting less than 30 minutes before being rapidly cleared from the bloodstream.

This could make it ideal for a short and focused therapy session skirting the need for intense monitoring by a healthcare professional, reducing costs.

“These characteristics allow DMT to stand out from other psychedelic compounds which typically generate a much longer psychoactive experience – the experience under psilocybin typically lasts six hours, LSD’s experience typically lasts 10 hours and ayahuasca 4-6 hours,” Rands said in an interview with pharmaphorum.

“We see this significant reduction in the duration of the dosing session as critical to the delivery of this treatment paradigm at scale in the future.”

The future of psychedelics in medicine

While these trials and others are a beacon of hope for the psychedelic therapy field and for patients in the grips of treatment-resistant depression and other disorders, there is a long way to go before such substances become market-ready.

Larger trials in far more diverse patient populations are needed and more need to be conducted head-to-head with existing and widely used treatments for mental illness.

For this, psychedelic research will require more investment and funding from public institutions and private investors, as well as clear regulatory pathways.

Regulator involvement will also be critical to increasing acceptance of psychedelic medicines as mainstream therapies and diminishing their reputation as “party drugs”. Now that the FDA has granted breakthrough therapy designation to treatments derived from both MDMA and psilocybin, the medicinal psychedelic field might just be poised to hit the pharma mainstream in the coming years.