Times were tough. Unemployment was high. People needed income.

While those descriptions might sound contemporary, they were among the factors leading to the creation in 1935 of America’s WPA, or Works Progress Administration, later known as the Works Project Administration. Originally started as part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “New Deal” program to counter the Great Depression’s 25% unemployment rate, the WPA is most commonly associated with public works like the construction of highways and bridges, or the Tennessee Valley Authority’s electrification of the South.

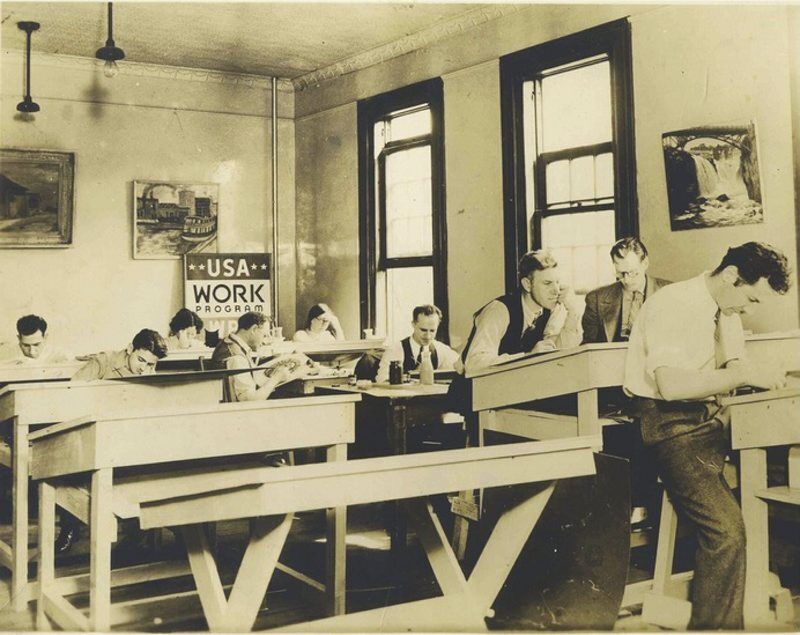

While WPA’s construction and manufacturing jobs employed millions, a lesser-known division of the WPA with just 500 workers also left a lasting legacy. It provided employment for commercial artists to create posters in support of the WPA program itself, as well as to disseminate a wide variety of public service information to the country. Based in 18 cities nationwide, this arm of the WPA produced 35,000 designs, resulting in an estimated 2 million prints during its seven years of existence.

Ennis Carter, founding director of Philadelphia’s Social Impact Studios in 1996, recently presented a virtual program about WPA posters, emphasizing those with a connection to the Ephrata Cloister, which sponsored the webinar.

Carter explained that, when her organization discovered that no record had been kept of the posters produced by WPA artists, it set about locating and cataloging them. Their index currently stands at 2,223 WPA posters. Among the results of this effort are a traveling “Posters for the People: Art of the WPA” exhibit, as well as a 500-page book of the same title, curated and authored by Carter.

Posters promoted a wide range of messages

Carter said that WPA’s poster artists were charged with creating visual “propaganda pieces” to attract the public’s interest through graphic designs, colors and simple written messages. She added that, while the term “propaganda” has acquired a negative connotation, by definition it relates to a system for propagating any doctrine, whether for good or for ill, with the artist at the center of how to influence the message.

The many messages propagated by the WPA posters were designed for the good of the American people during the Depression and World War II eras. Their subject matter covered a wide gamut. In Pennsylvania, the Fish and Game Commission made use of WPA posters that captured attention because of their beautifully illustrated subject matter to promote habitat conservation, hunting regulations and safety. A poster designed for Pennsylvania’s Department of Forests and Waters featured a colorful game bird with the message: Protect Bird Life, Prevent Forest Fires.

WPA posters fell into more than a dozen categories, including prosperity and opportunity, health and safety, American cultural traditions, and travel and destinations. There were posters about everything from baby care to being courteous to learning to speak English.

Some posters depicted good habits, such as “A Penny Saved is a Penny Earned,” while others touched upon world events as World War II approached. One poster, advertising the play “It Can’t Happen Here,” depicted a fire burning with a Nazi Germany swastika subtly imbedded in smoke from the flames. The poster’s message, “We read books instead of burning them,” was made for display at libraries. Another poster consistent with wartime messaging shows bright red lips with an “X” taped across them; it proclaims, “Careless Talk Costs Lives.”

At first, a WPA artist would design a poster and then other artists would sit together and copy it. This laborious process ended when Anthony Velonis, a former wallpaper company employee and WPA worker, introduced the screenprinting process used to make repetitive images on wallpaper. Utilizing this mechanism not only helped the WPA make more standardized, multi-colored images, but also allowed mass production and wider dissemination of their posters.

Visit the historic Ephrata Cloister

As world events during the 1930s became more dangerous, Americans’ travel abroad declined. Thus, WPA posters began encouraging travel and tourism within the United States, hoping to persuade travelers to spend their tourism dollars within the American economy.

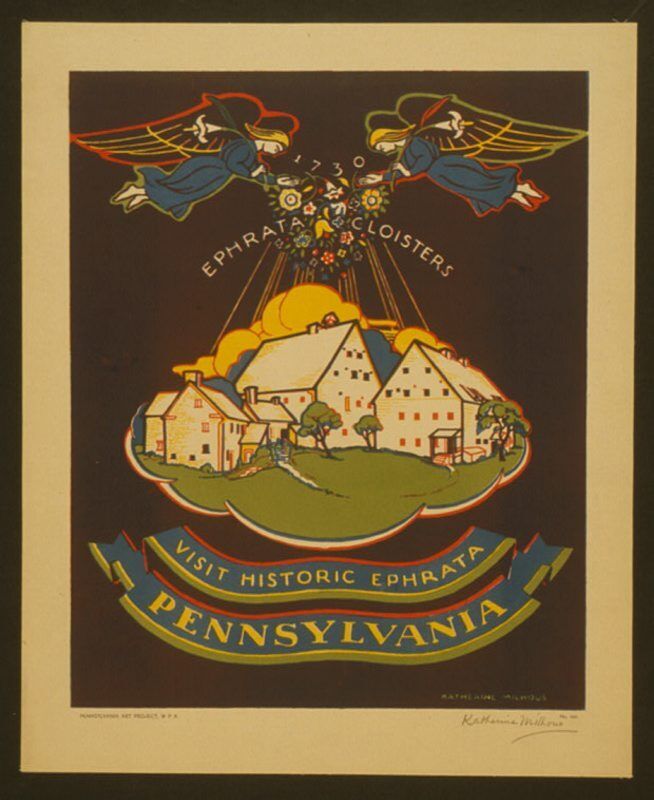

Philadelphia was one of the cities that was home to a WPA poster workshop. It was overseen by Katherine Milhous, a Pennsylvania native whose Quaker parents hailed from Lancaster and had operated a printshop. Milhous, already an artist of note, was tasked with having her team create posters that promoted Pennsylvania as a tourist destination. Among those created through this effort were two posters featuring the Ephrata Cloister, a state historic site once home to a monastic settlement of ascetics dating to 1732.

Perhaps due to her familial connections to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Milhous herself designed the WPA posters representing the Ephrata Cloister. In keeping with the simple lifestyle of the Ephrata Cloister community, she captured both the piety of its residents and the clean lines of their structures in her pieces. Although other WPA poster artists were not permitted to sign their works, Milhous was allowed to do so because of her established reputation and her position of influence with the poster project.

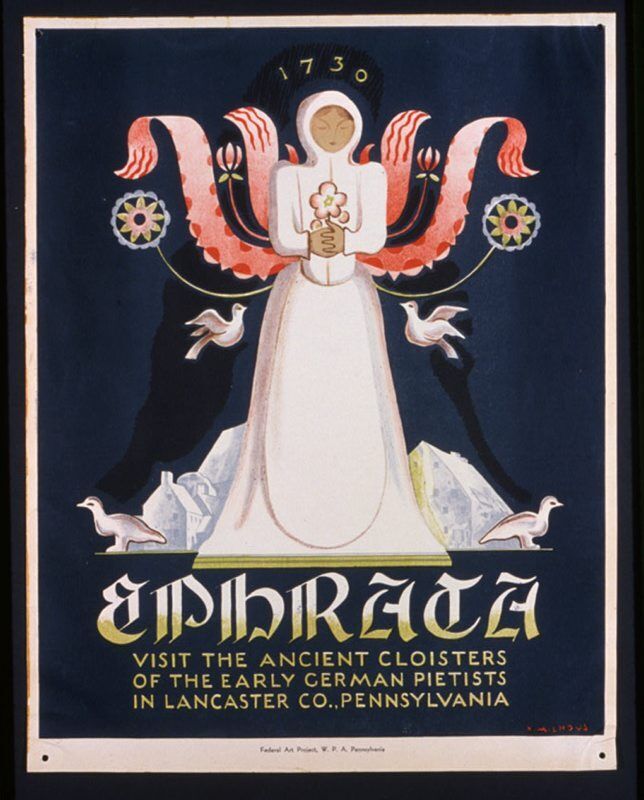

Photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Katherine Milhous’ lithograph of a monastic sister at the Ephrata Cloister community displays both the simplicity of the Cloister’s lifestyle and the beauty of Pennsylvania German influences, like the rosettes and bright petals of folk-art tulips.

One poster calls attention to the Cloister’s main buildings by using the poster’s off-white paper for their color, but contrasts that with the surrounding bright hues of blue, yellow, green and red. Hovering above the cluster of edifices are two angels clutching lilies and showering colorful flowers upon the community below.

This poster was printed in two versions with different colored backgrounds. While one is identified as dark brown and the other as deep red, both colors were achieved by mixing varied densities of the same blue and red inks to achieve these backgrounds, which highlight the main subject matter.

A second Milhous poster is less colorful, though equally striking. It contrasts a dark blue-gray background with the light-colored figure of a monastic sister at the Cloister clasping a single flower. She has four small doves at her sides with bright accents of vermilion that echo Pennsylvania German tulip petals around her upper body. Two small rosettes also recall the folk art of the Pennsylvania Germans, apparently further reflecting Milhous’ own familiarity with the traditions of Lancaster County.

The spare use of green accents lends a gentle depth to the Cloister sister poster and also calls-out its written text. The most prominent word is “Ephrata,” done in capital letters using a Germanic-style script shaded in off-white and green. The remaining green-colored text is lettered more plainly with the message, “Visit the ancient Cloisters of the early German Pietists in Lancaster Co., Pennsylvania.”

The sharper edges of these two posters’ images indicate that, instead of the screenprinting technique, they were produced by lithography, a printing process that uses ink applied to a stone or metal plate. Otherwise, their subtly shaded colors would have been difficult to achieve.

Another, unrelated depiction of the Ephrata Cloister was created by the WPA’s Fine Arts Division. It is a woodcut depicting silhouettes of Cloister community members approaching their buildings.

These works created by the WPA may be viewed online by going to the Free Library of Philadelphia website, http://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item and by searching “Ephrata.”

Carter encouraged anyone with a digital photo of a WPA poster to submit it to http://www.postersforthepeople.com/submit-to-archive.html, so it can be determined whether it has already been catalogued.