Viola Buitoni tried to help her son as he grew increasingly detached, the high school junior’s anger flaring, tears flowing as she begged him to do his schoolwork.

Before the pandemic, her son was thriving at San Francisco’s Ruth Asawa School of the Arts, where he was in the vocal music program and the robotics team.

But after schools closed in March, “everything came tumbling down,” Buitoni said. He has stopped going to Zoom school.

His glazed look scares his mother as she encourages him to do assignments or leave his room. “I can’t,” he responds. “It’s not, ‘I don’t want to do it,’” she said. “It’s ‘That’s too much effort. I can’t do it.’”

It is an all too common story across the Bay Area as school closures stretch on, with most large districts stuck in 100% online classes heading into a second year.

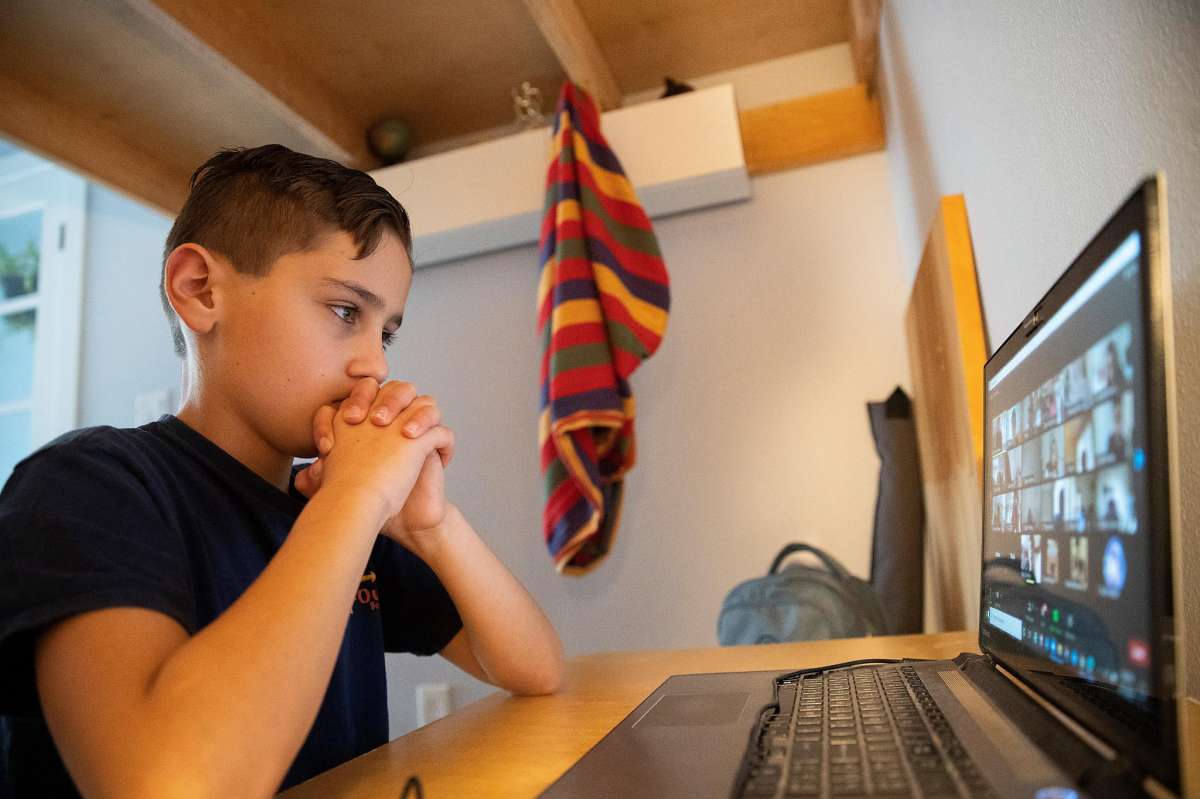

Senan, a fourth-grader, was at home in San Francisco instead of at school for his online drama class last week.

Santiago Mejia / The ChronicleOnce thriving children, with good grades, extracurricular interests and dreams for their future, started to disappear. They lashed out. Some stopped eating, or they started cutting themselves. Others, bored or without adequate technology, have stopped participating in school, their report cards filled with F’s.

They have stopped caring.

Parents have witnessed the academic, emotional and mental impact of shuttered schools — the lack of social interaction and in-person academic support apparent in their children’s behavior, attitude and grades.

In recent months, research and data have confirmed what families have felt: School closures have had a devastating effect on many children.

That has put increasing pressure on school districts to reopen, but moving toward in-person instruction has been complicated by a variety of factors, including vaccinations, logistics and timing. Unions and concerned parents have acknowledged the harm to students from distance learning but said without proper protocols and planning, they worry about the risks of in-person learning.

The harm is well-documented. In San Francisco, some students barely show up for class while hundreds have checked out of school, their whereabouts or enrollment status unknown, district officials said. Researchers estimate that across the country, 3 million students are academic no-shows.

Medals belonging to Senan Dokken, 9, who is at home taking his online drama class on Thursday, Feb. 11, 2021, in San Francisco, Calif. Dokken is in 4th grade in the city’s public school district. Schools continue to teach online, amid the coronavirus pandemic. Earlier in the week, an agreement was announced with the school district to reopen the city’s public schools. The agreement allows a return to classrooms once the city reaches red tier, the second most restrictive level of California’s reopening blueprint, if vaccinations against the coronavirus are made available to school staff. If the city progresses to the orange tier, a less restrictive category with “moderate” virus spread, teachers and other staff would return without demanding vaccinations.

Santiago Mejia / The ChronicleThe impact has also been staggering at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, where emergency room visits and hospitalizations for mental health issues have doubled over the past year, according to Dr. Jeanne Noble, UCSF director of COVID-19 response.

Pre-pandemic, ER doctors might see a suicidal adolescent every few months; now it’s virtually every shift, said Noble, who is also an emergency care physician. During a recent shift at Kaiser Richmond, three children between the ages of 10 and 13 arrived at the emergency room with cuts on their wrists.

“It is a horrible cry for help,” Noble said. “Three middle-schoolers in one shift, screaming from the rooftops, is unusual.”

Local, state and national health officials have increasingly called on education officials to reopen classrooms as soon as possible because it’s not just about learning, experts say — it’s also about in-person socializing with peers and teachers, child care, food security, physical safety, mental health resources, exercise and play.

Those officials have repeatedly said that reopening can now be done safely. But across the Bay Area and the state, the debate continues to rage, based on each school district’s and labor union’s definition of what is considered “safe enough” to reopen.

But parent and teacher Christine Kratt said educators have been scapegoats for the failures of lawmakers and leaders.

From left: Erik Dokken as his son Senan Dokken, 9, stretches during his online drama class on Thursday, Feb. 11, 2021, in San Francisco, Calif. Senan is in 4th grade in the city’s public school district. Schools continue to teach online, amid the coronavirus pandemic. Earlier in the week, an agreement was announced with the school district to reopen the city’s public schools. The agreement allows a return to classrooms once the city reaches red tier, the second most restrictive level of California’s reopening blueprint, if vaccinations against the coronavirus are made available to school staff. If the city progresses to the orange tier, a less restrictive category with “moderate” virus spread, teachers and other staff would return without demanding vaccinations.

Santiago Mejia / The Chronicle“We’re being blamed and attacked by armchair epidemiologists,” said Kratt, of San Diego, speaking at a recent news conference organized by the California Teachers Association. “I need to believe strongly when I put my child back into a classroom that every single thing that can be done is being done.”

While many districts have opened in the purple tier, the most restrictive in the state, some labor unions want to wait until the yellow tier, the least restrictive. The Oakland teachers union, for example, proposed reopening only when case rates are “near zero,” a demand that far exceeds all local, state and federal health requirements.

But while the district and Oakland Education Association continue negotiating over reopening, they are also considering an interim step that would allow some teachers to return to classrooms with small groups.

If you need help

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: Call 800-273-8255 to reach a counselor at a locally operated crisis center 24 hours a day for free.

Crisis Text Line: Text “Connect” to 741741 to reach a crisis counselor any time for free.

Union officials say teachers have worked valiantly during the pandemic to ensure students are learning as much as they can remotely, and in-person learning would expose staff — including those who are older or who have pre-existing conditions — to a virus that has killed nearly 500,000 people nationwide.

Oakland school board President Shanti Gonzalez said she worries about special-needs students who are struggling without in-person support and who could return in limited numbers.

“It’s very urgent that we get back to schools as soon as possible,” she said.

But it won’t be soon.

While thousands of districts in Marin and other counties have had students back in classrooms for months, those in San Francisco, Oakland, Pleasanton, Berkeley and the majority of urban districts in the state are still weeks or months away from in-person learning, if at all this academic year. It depends in part on the availability of a vaccine and the willingness of teachers to come back with or without one.

Meanwhile, the academic toll on young people, especially students of color, those from low-income families and English learners, is compounding, researchers say.

Across California, students in elementary and middle school are experiencing significant learning loss, according to a report released in late January. English learners and students from low-income families have seen greater losses, according to Policy Analysis for California Education, a nonpartisan research center, which looked at 50,000 students from 18 districts.

While not all students are suffering learning loss, the impact on some has caused an “unprecedented disruption” to their education, according to the researchers.

“What we knew is that there are some kids that are suffering more than others during this time,” said Heather Hough, one of the authors and a researcher at Stanford. “Some kids are falling behind very quickly.”

Hispanic, Black or multiracial students said it was harder to focus on school than did white or Asian American students.

Oakland kindergarten teacher Bonnie Forbes Wittenstein said the year has been a huge setback for her students.

“So much of kindergarten is learning to make friends and interacting with other kids their age,” she said. “That’s why we do kindergarten.”

Instead, her students talk to her or other students five minutes a day. In person, they would be talking all the time. The English learners are unable to get the time, practice and attention on language learning, she said.

“Teachers like me who are ready to go back should have the right to do their jobs,” she said.

The negative health, academic, social and other consequences of the pandemic on children should be part of that equation, experts say, with in-person instruction as essential as grocery stores, public transit and post offices.

Full-time single dad Erik Dokken said he has turned down handyman jobs to be home with his 9-year-old son, Senan. A few times he’s left his son home alone to do a job or taken him along. It hasn’t gone well.

“It’s quite stressful and quite emotionally taxing,” said Dokken, who lives in San Francisco. “It’s impossible for me to make a penny unless I’m away from home working at someone else’s house.”

In those homes, he sees toys, evidence of children, but they aren’t there — they’re enrolled in a reopened private school.

He worries about Senan, who sits in front of a screen all day.

Noble said the impact of virtual learning has reached crisis proportions.

“How are we continuing to say we’re keeping kids safe at home, locked up in bedrooms in front of computer screens?” she asked. “What is happening to the brain development of all these teenagers shut in their dark bedrooms on Zoom all the time?

“We basically know those kids are harmed for life.”

Jill Tucker is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: jtucker@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @ jilltucker