Feeling sad. Sleeping too much. Not wanting to do things that used to be fun. Such feelings may come and go throughout adolescence. But if they last more than two weeks, they can be signs of depression. It’s a serious mental health disorder that requires treatment. And it’s remarkably common in teens. By age 18, one in four will experience at least one bout of depression. In fact, that may not be surprising, since stress appears to be a major trigger.

People sometimes think of depression as sadness. Some people with depression do feel sad. But many also lose interest in everyday activities. They don’t get excited about things they once enjoyed. They lack motivation. They just feel sort of … empty. They may have trouble sleeping, or sleep too much. They may even eat more — or less — than usual.

Most also spend a lot of time replaying negative events. This and focusing on negative thoughts are known as rumination (Rue-mih-NAY-shun). It gets people thinking too much on what seems to be going wrong in their lives. Such thoughts feed back on themselves in a loop, getting worse and worse.

Scientists don’t know for sure if rumination causes depression. But “if it doesn’t cause depression, it certainly perpetuates it,” says Ian Gotlib. He is a psychologist at Stanford University in California. Gotlib is one of many scientists trying to understand teen depression.

People are diagnosed with depression when they experience at least five of nine main symptoms. These include depressed mood and loss of interest or enjoyment in activities. Altered sleep patterns and appetite. Overall low energy. Anxiety and trouble concentrating. Feelings of guilt or low self-worth and thoughts about death. Some are more common than others, but few people experience all of them.

The various mixes of these symptoms number in the hundreds, Gotlib says. And that can make depression tricky to treat. Treatment that works for a teen with one set of symptoms might not work for an adult with a different set. Depression researchers are learning that different changes in the brain may be tied to specific symptoms. When those changes happen during adolescence, they can lead to long-term mental-health issues.

But there’s good news, too. The flexibility of the developing brain means teens may be able to prevent long-term problems if they seek help.

All about rewards

The human brain changes a lot between childhood and early adulthood. It grows and develops during this time. But different areas mature at different rates.

Areas involved in processing emotions mature early. They are part of what’s known as the limbic system. Gotlib likens it to an engine. This system is what gets us revved up and going. The prefrontal cortex, in contrast, acts like the brakes. It tries to exert self-control by tamping down the limbic system’s impulsive urges. But the prefrontal cortex takes longer to mature — well into someone’s twenties.

Part of the limbic system plays a role in motivation and rewards. One area in particular is the ventral striatum (VEN-trahl Stry-AY-tum). This area lies deep inside the brain and influences whether we want to try something. If we do try it, it also affects how much we enjoy it. This area is one reason teens tend to be impulsive. They focus on the thrill but don’t yet have a good grasp of the risks.

If the ventral striatum isn’t functioning correctly, it may contribute to depression. That’s because this region is essential for excitement, anticipation and enjoyment. If we don’t feel those emotions, we lose interest in the activities that once sparked them. The resulting apathy is “one of the key symptoms of depression,” says Deanna Barch. She is a psychologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Mo.

But the ventral striatum doesn’t work alone. It partners with two other areas thought to help process rewards. The anterior cingulate (SING-gyew-let) is part of the limbic system. It helps us make decisions, control impulses and regulate emotions. Then there’s the parietal (Pu-RY-eh-tul) cortex. It’s involved with self-awareness. All three areas act together when we anticipate something good or bad. They also register when something good or bad actually happens.

How the brain measures rewards

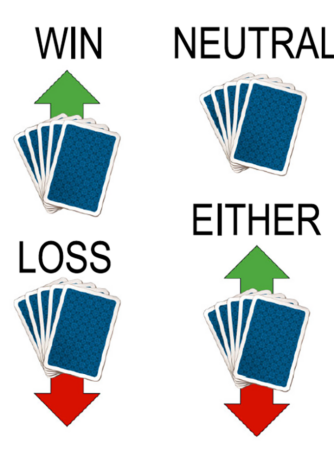

Barch wanted to know how depression affects reward regions in the brain. She teamed up with psychologist Katherine Luking, also at Washington University. Their group worked with 100 teens who were 16 to 18 years old. Barch had been working with them since they were young children. For this study, the teens came into the lab to play a virtual card game.

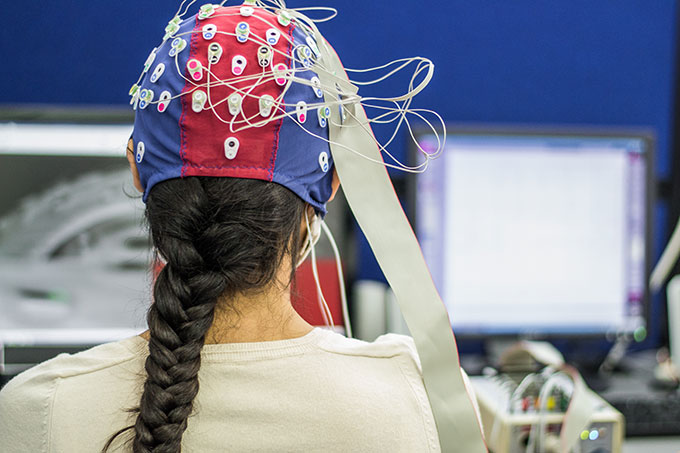

The team told the kids they would win money if they guessed correctly whether they would win or lose each round of the game. The teens got a hint ahead of time to help them with their guesses. While they played, the kids wore a net of electrodes on their heads. It picked up electrical impulses from different areas of their brains. The electrodes allowed the researchers to see in real time how these brains responded to wins and losses, especially in the reward regions.

Kids who first experienced depression as teens didn’t have a big response to wins. But their response to losses proved strong. “They hurt more,” Luking explains. That could be because they felt sad or down, she notes, and those feelings were exaggerated when they lost.

Teens who first experienced depression in preschool, on the other hand, didn’t show much brain response to wins or losses. This might link to feelings of apathy, Luking says. “You get a ‘numbing’ effect to both types of feedback with that specific symptom,” she notes. For these kids, there’s no joy from a win. But a loss also doesn’t sting.

Barch and Luking think early life experiences play a role in setting up later feelings of apathy. If you are unable to enjoy things early in life, Barch says, it may “set up your brain to be less responsive to good things in the future.”

Their findings are supported by other research.

Several studies, for instance, find that early life stress, such as neglect or abuse, may set children up for depression later. Others find that a stressful event in adolescence or later triggers the disorder. Some scientists think there are two parts to developing a mental disorder, Gotlib says. The first is some type of vulnerability. This might be genetic. Or it might be one of those stressful events early in life. The second is experiencing major stress later in life. That might be losing a loved one, for example, or being bullied.

“You can have a genetic predisposition to depression,” Gotlib says. But “unless you experience a significant stressor, you may go through life without ever developing the disorder.” On the flip side, someone who is not predisposed may experience stress but not develop depression, he notes. Both parts are required to trigger the changes that lead to depression.

Making connections

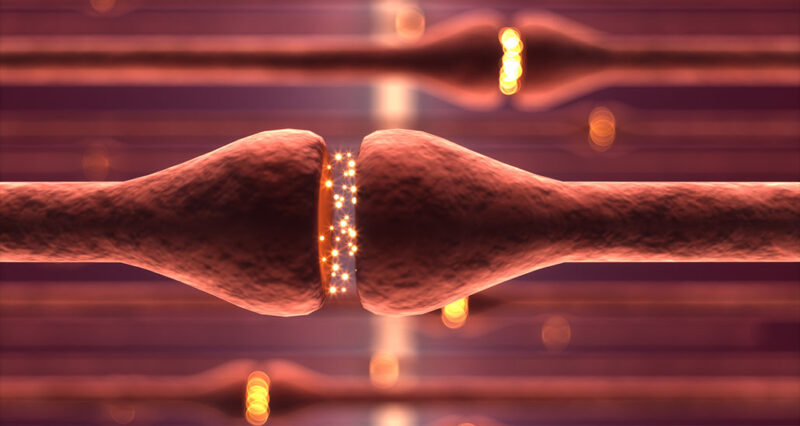

Changes in a teen’s developing brain may make it extra sensitive to stress. The brain contains billions of neurons. During development, these cells grow long extensions called axons. The ends of axons send signals to other neurons. They do this by releasing chemicals called neurotransmitters. This is how the brain’s neurons “chat” with each other.

Many connections form within a single brain region. Others connect one region to another, like long-distance highways. Most between-region links form early in life. But those between the limbic system and prefrontal cortex connect during adolescence. This is when the brakes begin to slow down those emotional impulses.

All of that happens in the brain of every teen. But add in depression and you have a recipe for long-term mental-health issues. That’s because depression appears to alter how brain connections form. That’s true within the prefrontal cortex, notes Cecilia Flores. She is a neuroscientist at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. Even more importantly, she adds, it’s true of links between brain regions.

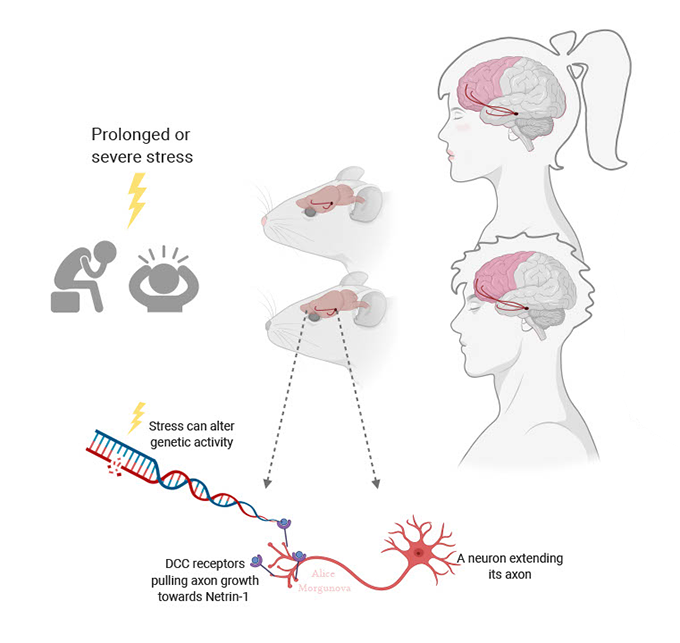

Flores has been trying to understand what guides axons as they grow. How do they know which brain regions are the “right” ones to which they should connect? How do they know to start chatting with one neuron instead of another?

The brains of rodents and primates show similar connections. So Flores and her lab study them in adolescent mice. The advantage to using mice is that the researchers can later look inside their brains. They can track neurons from one place to another. They can probe for specific molecules that affect neuron growth. And they can see what might be causing changes in behavior.

As in people, stress can change the behavior of mice in ways that resemble depression, the team found. For example, mice normally choose sugar water over plain water. But when stressed, they no longer prefer the sugary option. Mice also are social. But “depressed” mice don’t socialize when given the chance.

The brain connections in mice showing these behaviors are also different. Flores and her colleagues focused on two brain chemicals: DCC and Netrin-1. Both help guide growing axons to the right target. They also are abundant in neurons that respond when people (and mice) expect or get a reward.

These neurons use the neurotransmitter dopamine. “Dopamine connections are very important” in reward processing, Flores says. Together, DCC and Netrin-1 choreograph new connections between those neurons and the prefrontal cortex, she explains. And they are especially active during adolescence.

Stress can cause Netrin-1 and DCC to show up in the wrong regions of the brain, she and her team reported last year. When this happens, some axons connect where they normally wouldn’t. Connections may break between some neurons while new links form between others.

DCC levels usually drop off in adulthood. This appears to stabilize and protect brain connections, Flores explains. But DCC may not drop in the brains of depressed people or stressed mice.

She and her team examined brains of depressed people who died by suicide. They found high levels of DCC in the prefrontal cortex. This suggests that connections in these brain regions are continuing to change, she says. That in turn could disrupt the balance of emotional impulses and brakes — and lead to mental-health problems. But a lot is still unknown about how this may happen, she adds.

Controlling stress

Study after study finds that stress can trigger depression. In a recent one, Flores’s team found a possible link between stress and DCC. A tiny molecule called miR-218 can tamp down DCC levels in neurons. But stressed brains have less miR-218. That boosts DCC levels as well as brain changes linked to depression-like behaviors.

Her team described its findings last October 15 in Biological Psychiatry.

When stress suppresses miR-218 in the teen brain, “we see changes in DCC but in a brain that is still developing,” Flores says. “So the consequences of the changes we see are large.” Axons meant to connect two brain regions may now grow in the wrong direction. This can create a brain that’s not “wired” correctly.

In adults, changes tend to be more localized to within a region. And the effects are “not as large because connections between distant regions are already formed,” she says. Such altered wiring during the teen years may be related to why people who first experience depression in adolescence are more likely to have recurring bouts as adults.

Right now, psychiatrists treat depression by prescribing one treatment and seeing if it works. If it doesn’t, they try another. Most people respond to some type of therapy, but it’s not always the first one they are prescribed. Flores hopes her research will take some of this guesswork out of treatment. It may help point to what will work best based on the brain changes underlying a patient’s symptoms.

One day, scientists might identify ways to prevent axons from connecting the wrong way in the first place. This could reduce mental-health problems the world over.

For now, there’s hope. “The brain is still very malleable in adolescence,” Flores says. Wiring problems have time to be fixed before the brain fully matures. Teens “can take advantage of that,” Flores says. “Be exposed to a good environment, healthy experiences, enrichment.” Each will benefit your brain in the long term.

“Talk to somebody if you start feeling down and depressed,” Gotlib adds. Depression “is among the most easily treated of all psychiatric disorders” — as long as people seek help. For many people, talking to a mental-health professional may be enough to restore normal feelings and behavior. Others may require medication. “There are a lot of options that work,” Gotlib notes. Seek help and know you’re not alone.

Important note: As of 2016, suicide is the second leading cause of death among young adults ages 15 to 29. If you or someone you know is suffering from suicidal thoughts, please seek help. In the United States, you can call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline, 1-800-273-TALK (8255). Or you can text 741-741. Please do not suffer in silence.